Many Central and Northern European countries have district-heating systems where the community’s needs for hot water and space heating are met by metered heat piped from a central source such as a boiler or CHP plant. Such systems are highly suitable for a centralised biomass-fired co–generation of electricity and heat.

In comparison, Ireland has few district heating systems and all were established with some form of public support . The demand for home heating in Ireland is dispersed due to a pattern of low density housing development with many one-off or standalone houses. This scattered distribution of housing in Ireland greatly enhances the cost of providing district heating. Further barriers include a lack of an existing infrastructural network for district heating and the need for financial investment and support, combined with a lack of indigenous knowledge or planning guidelines specific to district heating, although this may change in coming years .

The greatest potential for district heating in Ireland is in large–scale schemes that target apartments and services (in Dublin) as well as small–scale high occupancy buildings in the rest of the country located where more expensive existing heating sources prevail (i.e. that are not connected to the gas network). The Tralee Town Council District Heating scheme is a good example .

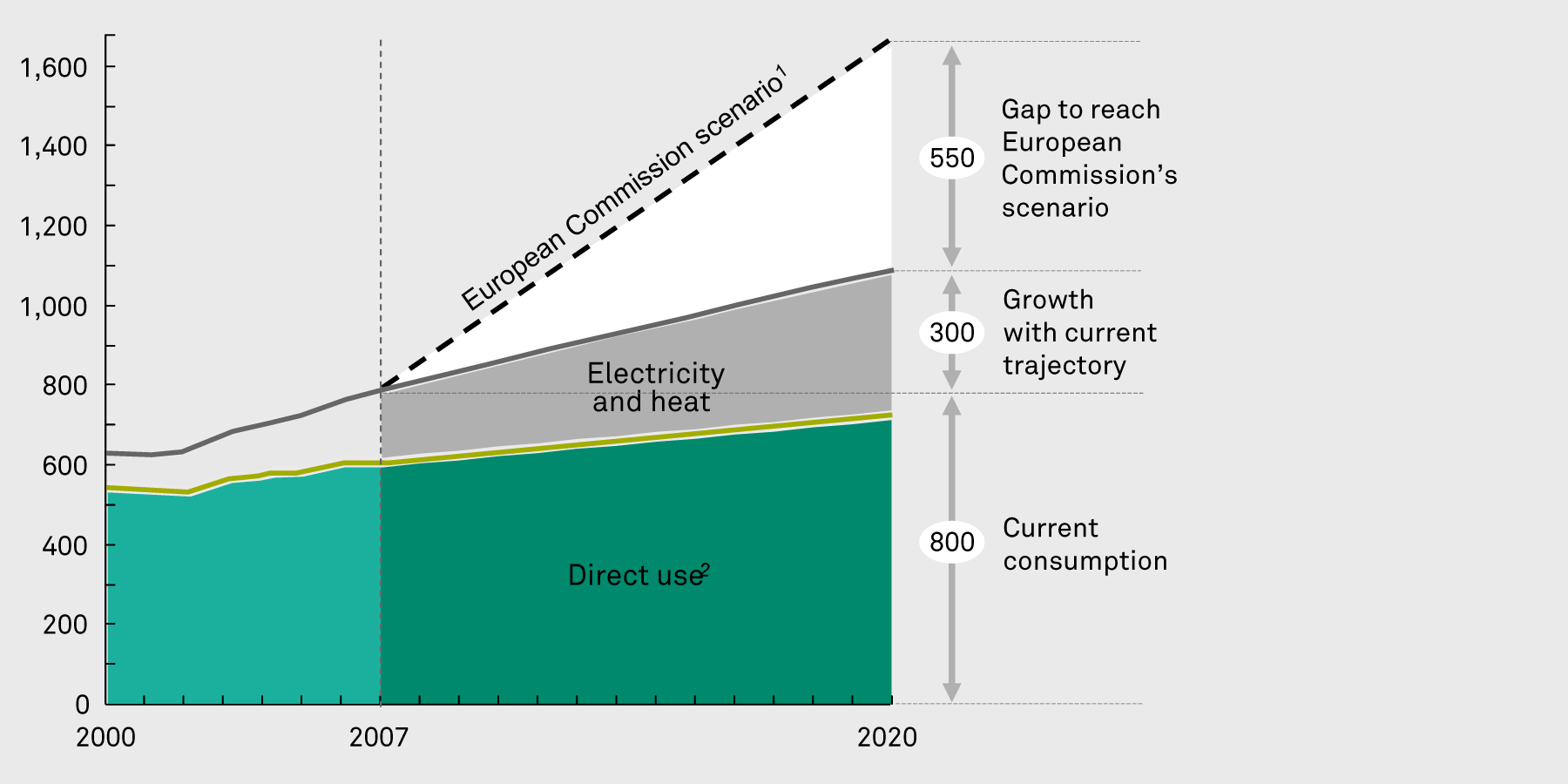

Recent SEAI analysis indicates that without further policy measures, the RES-H 12% target will not be reached. The estimated shortfall is between 1 and 5 percentage points across a number of scenarios depending on fossil fuel prices and cost competitiveness of renewable heat technologies.

The renewable heat sector is for the most part underdeveloped with less deployment of biogas and solid biomass than needed to meet our targets for renewable energy in heat. Since 2006 there has been a 2% average annual decrease in industrial renewable heat, although biomass energy use in the residential sector has increased by 9.5% between 1990 and 2011.

Current policies such as REFIT supports, energy efficiency goals and, taking into account natural migration to renewable heat technologies, will not deliver the 12% renewable energy target in the heat sector by 2020. Previous support programmes which incentivised the uptake of renewable heat such as the SEAI Greener Homes Scheme and the ReHeat programme have expired and have not yet been replaced. The Government’s Bioenergy Plan has been published, albeit in draft form until a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is completed, and the Renewable Heat Incentive is awaiting EU approval .

The proposed exchequer funded Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme for larger non-ETS industrial and commercial renewable heating installations is expected to contribute to meeting the 2020 target. According to the SEAI, the most cost-effective option for renewable heat under the incentive is the replacement of oil in large industry and supplying commercial sites with biomass boilers. Additional uptake of heat pumps in the commercial sector would also be needed.

Initiatives and opportunities for the conversion of public sector buildings to convert to bioenergy heat supply contracts were also proposed in the Governments draft National Bioenergy Plan . A final version will be finalised by 2017.

Could we make more use of biomass in power generation and CHP?

The biggest user of biomass for energy purposes in Ireland is the Edenderry Power electricity generating station, which co-fires biomass and peat. There is further potential for peat substitution by co-firing biomass at the two remaining peat-fired stations operated by the ESB.

Several large users in the wood processing industry have established combined heat and power plants (CHP) to meet their heat requirements while exporting surplus power at attractive rates . There are two such commercial wood-fuelled CHP plants in Ireland, one at Grainger Sawmills and the other at Munster Joinery in Co Cork . In County Mayo a developer is building a 42.5MW biomass high efficiency CHP plant .

These plants were incentivised as a means to generate renewable electricity through the Renewable Energy Feed in Tariff (REFIT) scheme, the 3rd version of which is currently underway. While previous versions have focused on other renewables such as wind, hydro, and waste, REFIT 3 is designed to incentivise bioenergy. REFIT 3 aims to support the addition of 310MW of electricity capacity by combined heat and power (CHP), biomass combustion and biomass co-firing , 44 MW of which were supported in 2015/16 by the Public Service Obligation (PSO) levy, funded by electricity consumers via a surcharge on electricity bills . REFIT is designed to provide price certainty to renewable electricity generators, paying the difference between the wholesale price and the guaranteed REFIT price ,. The main expenditure in the biomass fired CHP supply chain is fuel supply and dedicated supply chains, whether domestic or international depending on availability or price.